Share:

Parallel Public is a new publication by Sara Blaylock, published by MIT Press. The book documents the East German artists pioneering work that made their country’s experimental art scene a form of (counter) public life.

The book originated as the doctoral dissertation, which I defended in spring 2017. The research began in earnest in summer 2012 when a German Studies Research Grant from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) afforded me the opportunity to spend about two months in Berlin. I returned to Germany for 10-month and 5-month stays in 2014/15 and 2016. As you’ll note from the rather long list of archives and interviews, not to mention the names noted in my acknowledgements, the research for this book was pretty elaborate (hence my lengthy answer).

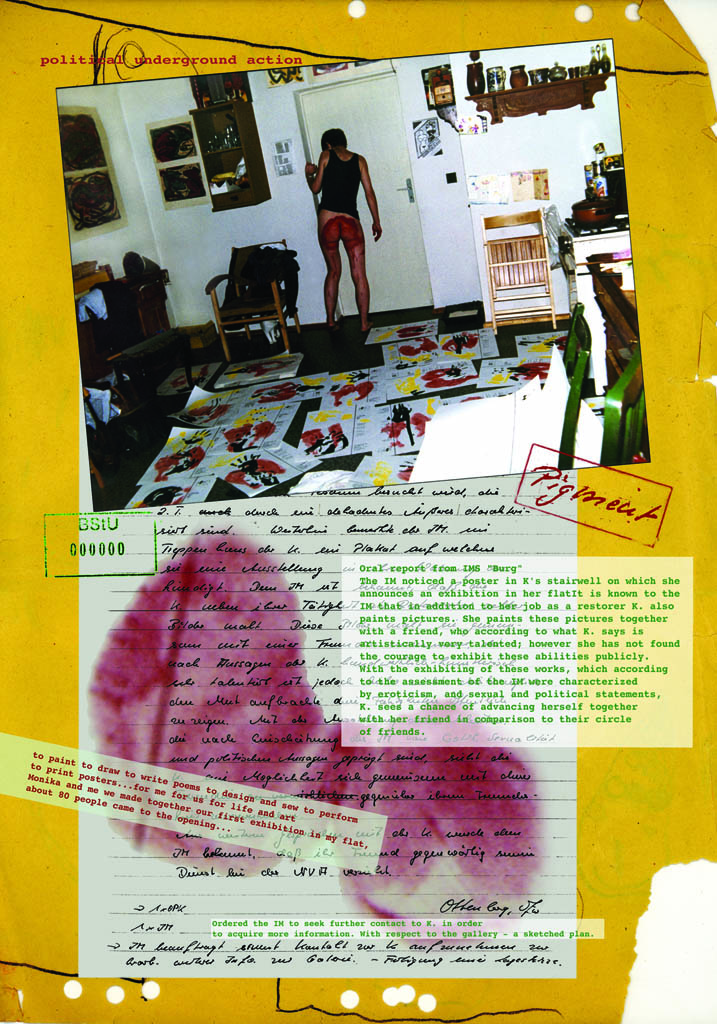

In addition to the artwork itself, Parallel Public draws from four major sources: (1) interviews with more than two dozen artists, art historians, writers, and organizers; (2) artist-made publications; (3) official reports by the Union of Fine Artists, including articles from its flagship publication Bildende Kunst; and (4) Stasi surveillance records. I can elaborate on how instrumental the forming of personal relationships with artists, curators, and other scholars was in the research and writing of this book. To take one example, access to surveillance files requires permission from the person observed; it often took time to get those permissions. To take another, less obvious example of the methodology, a large portion of what appears in this book comes from people’s personal archives and memories. I have at least enough material to write a second book!

I note this because it helps me answer the second part of your question. From the very first interviews I had with artists and their contemporaries I very quickly recognized the desire people from the former East Germany had to see a more complex historical accounting of their creative lives. Having been a part of some really interesting non-commercial art spaces in the Bay Area of the early to mid 2000s, I also found familiar the ways that the GDR’s experimental artists used spontaneity, including their innovative use of materials and space.

Also interesting for me was the tenacity of that the experimental scene; there were a lot of roadblocks (censorship, fines, legal punishment) that organizers and artists confronted and really stepped around.

It also is very clear, in reviewing the extant literatures on Cold War era German (not just East) art, as well as the exhibition histories of East German artists since Germany reunified in 1990, and in conversation with other scholars (both in Germany and in the US), that this history really warranted a new approach. I had a nice distance as an American; I am not tangled in the somewhat palpable rifts that persist between those who believe nothing interesting could have ever happened in communist Germany, and those who lived in that space and actually did make things happen.

In so many ways! In fact, my research demonstrated to me that artists were emboldened by the risks taken by those who preceded them. So, a gallery like EIGEN+ART, which was obsessively surveilled by the Stasi but never shut down, achieved a high level of visibility even in a context that officially said independently run galleries could not exist, because its founder, Judy Lybke, could draw from the techniques used by artists who came before him. These techniques often amounted to a very careful understanding of how the GDR’s cultural bureaucracies worked. So, for example, Lybke registered his gallery as a studio of an artist named Akos Novaky who was in the official Union of Fine Artists, which granted all of its members a studio space. People who created independent publications were also emboldened by special dispensations afforded to artists to create “artist portfolios,” which were not considered to be publications that needed to be registered with the state. These producers also found ways to work around copy restrictions, for example, asking contributors to each produce copies of their own work (photography, artist prints, and also texts). It’s all pretty uncanny when you think about the narratives of the GDR that dominate; also very savvy.

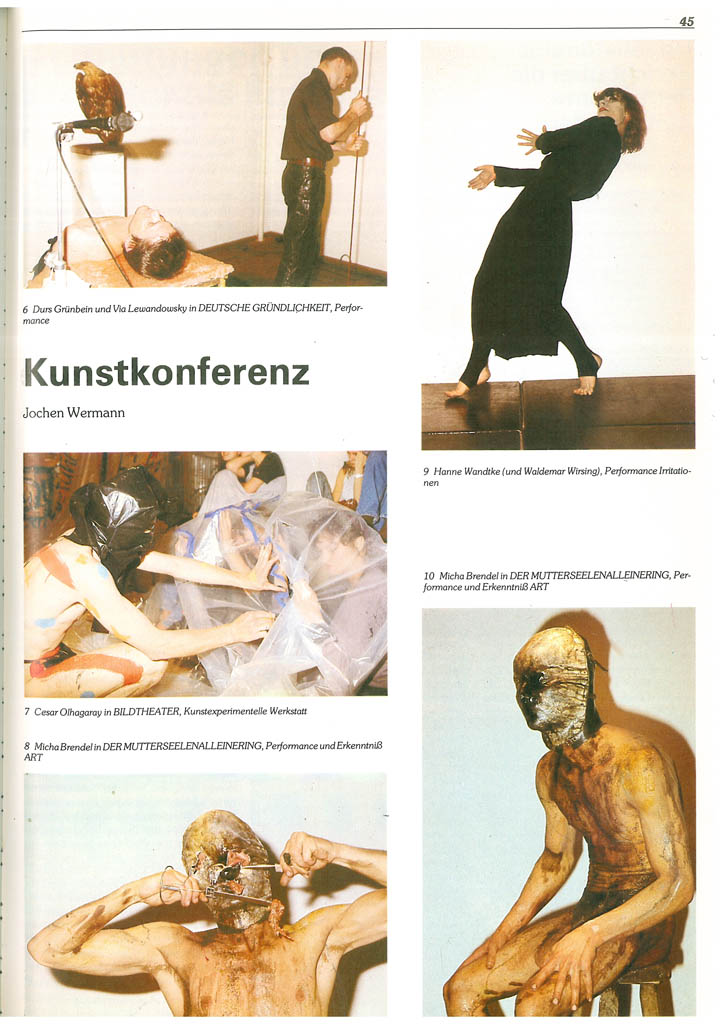

I’ll end this answer by addressing the way that artists also used the official channels of art making to support and expand their art. Not all of them, but many of the people I describe studied art at official schools. This meant that they could follow a pretty direct route to professionalization as an artist in the GDR. Completing a degree meant candidacy into the Union of Fine Artists, as well as access to commissions, studio and rental subsidies even in the candidacy period. Among my favorite stories is the way that the Auto-Perforation Artists managed to use the art academy in Dresden as a platform for the presentation and eventual acceptability of performance art as an officially recognized art form. These artists, who–as their name suggests–explored abject substances, self-harm, as well as explorations of gender and class, are about as far afield from Socialist Realism as you can imagine. And yet, their work appeared on public, not underground stages.

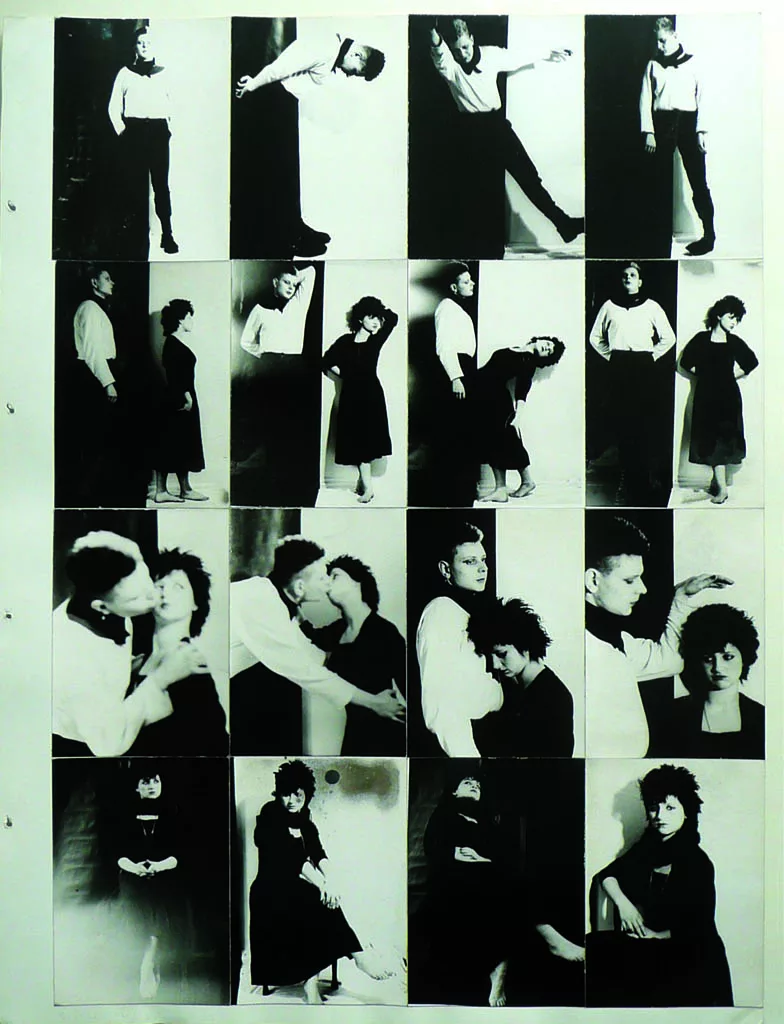

I will close to say that life as much harder for experimental artists in the earlier part of the 1980s. Important here is the case of Cornelia Schleime, whose film work as well as a 1992 series of photographs/prints she made with her Stasi File I explore in my book. Schleime actually turned to film in the early 1980s after she was effectively banned from exhibiting her paintings. Even here, we can see the perseverance, namely the adaptability of an artist who really wanted to be an artist and who really loathed living the GDR. She found a new way to reach a public, and even sought to coerce the Stasi watchers she anticipated in her midst.

The publics increased incrementally, and this is not to say that artists in the GDR had the kinds of consistent audiences a person might expect today, let alone in a contemporaneous Western context. They used publications to share work (this was especially true for writers, but in fact, photographers and printmakers also got a good amount of coverage through their participation in publications). Approximately thirty independent publications (meaning discrete titles) appeared in the GDR between 1979 and 1990. By the final years of the GDR, these publications were actually being collected by the state library in Leipzig. These independent publications (what some call samizdat, borrowing the term for a coinciding movement in the Soviet Union) became increasingly incisive, with more critical and theoretical texts / concepts appearing in the final years. So, whereas in 1979 it was a big enough deal to just put artists together in a publication, by 1989 these venues were more discerning. This also reflects a shift in the risks associated with self-publishing. In fact, we can witness a similar change in independently run exhibition venues, which became not only more public-facing and numerous, but also more selective in what works would be put on display.

Here it is important to note that nearly all of the artists I describe in my book also participated in the GDR’s official cultural scene. So, a photographer like Gundula Schulze Eldowy, who made very frank portraits of labor, love, and aging, actually published some of her work in official state magazines and showed some of her work in official state galleries. For many, the operative word is “some” here. Meaning, artists understood that official venues required a little bit of a lighter touch in terms of controversy. On the other hand, the Auto-Perforation Artists mounted an exhibition in early 1989 entitled Mentekel (which I translate to Bad Omen) at a state run gallery. The space included thinly veiled references to state oppression in, for example, a room lit by hot red theater lamps that led to an aquarium filled with proletarians and farmers tilling the land. Also featured were a good dozen cow legs cut at the hock joint afixed to shards of glass. The state tried to shut down the show because of these animal parts, which began to rot. They failed in that attempt. Three of the core members of the Auto-Perforation Artists (which was basically comprised of four people) actually received admission to the Union of Fine Artists because of this show. I can see the power of artistic tenacity in that outcome!

I think the most obvious answer would be to describe when Else Gabriel of the Auto-Perforation Artists dunked her head in a vat of pig’s blood mixed with emacerated meat and gummy bears…but I’ll offer something a little more community-based. Happy to elaborate on the former, however, if you like.

On June 1 and 2 1985, two organizers (Micha Kapinos and Christoph Tannert, who is the long-time Artistic Director of the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin) organized the Intermedia 1 Festival, a gathering of music, live art, and painting at a state-run cultural centre in Coswig, a town located a short distance by train from the city of Dresden. Billed officially as a jazz festival, Kapinos and Tannert actually had received permission to stage their festival, but state authorities balked against its contents after the fact. Dozens of artists were involved and hundreds attended.

The Stasi file on this event includes a good deal of photographic documentation. In fact, the picture on my book’s cover comes from that documentation. You see in this image that the Stasi mole (a so-called “unofficial collaborator”, so not a person who actually worked for the Stasi in an official capacity) was friendly with the people they (he, more than likely), photographed. The camera operator is playing around with the person capturing his image; a kind of playful camera-on-camera moment. The woman, who you see on the back cover is smiling at the camera. Importantly, neither the man or woman would have known that the person taking their picture was doing so on behalf of the Stasi. Ultimately, the event led to a number of arrests and the firing of the clubhouse director. A good wave of artists also left the GDR after the perceived failure of the event; it is not remembered fondly by many. In fact, Tannert explains that Intermedia 1 was meant to be followed by future iterations.

However, the impacts of the punishment would not last long. Tannert, who had lost his job in the Union of Fine Artists, quickly found another, arguably better job as a freelance writer for the official state art magazine Bildende Kunst. Intermedia 1 may have disappointed a slightly older subset of artists, including people like Lutz Dammbeck whose multi-media performance/installation Herakles opened the weekend, but for younger people, it triggered a greater commitment to experimentation. With so many people gathered together, new connections were made…the event was rhizomatic, and its impacts unstoppable.

The event was thus controversial to the state, and also not necessarily beloved by all, but it nevertheless led to a sea change in creative productivity. This is particularly evident in a shift to multi-media practices and live or body-based works. The term, Intermedia, was of course borrowed from a narrow understanding of the Fluxus movement’s idea of “intermediality.” For the GDR, when artists media they confronted the conventions of state culture on a number of levels.

My colleague, friend and collaborator Dr. Sarah James (author of Paper Revolutions, forthcoming with The MIT Press) are in the beginning stages of an edited volume that engages a potential theme of thinking about the DDR in terms of speculative futures, utopianism, decolonialism, solidarity campaigns, and activist ecologies. The project actually comes out of a collaborative writing project Sarah and I did as part of an exhibition we co-curated (Anti-Social Art: Experimental Practices in Late East Germany), specifically the creation of its catalog, which is really a freeform experiment. Sarah and I hope to get our book proposal together this summer and have a few presses interested. Stay tuned!

You can purchase the buy here.